IslamoPop and the Plight of Palestine: An interview with Laila Shawa (Originally published in Hard Magazine)

Does the significance of an item of clothing change along with the body that wears it? IslamoPop artist Laila Shawa addresses this very question with her body of work.

Renowned Islamic art critic Dr Christa Paula has described Shawa as “one of the few Arab artists to successfully break through the barriers of the West.” Laila Shawa, a self-professed IslamoPop artist, is now working in London and her work covers a myriad of post-modern themes. Shawa is an established Palestinian artist who was born in Gaza in 1940, making her eight years old when the state of Israel was declared. Her many solo exhibitions include _The Other Side of Paradise_ at the October gallery in 2012 and she has just featured in Art Dubai 2013. She explores issues like the position of women in the Arab world, as well as the exploitative commodification of ideas in relation to Palestine. I was keen to find out just how such a fun-loving movement like IslamoPop can tackle the serious issues Shawa is interested in. In March, I met Shawa at ART13 London in Kensington where I probed her about her work.

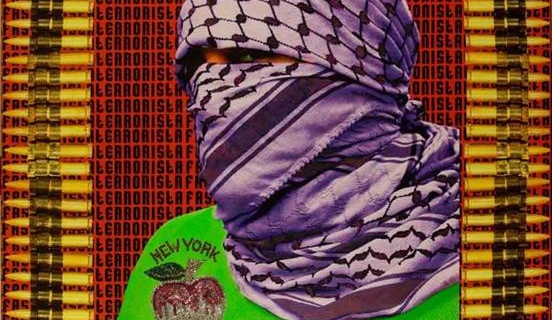

Hanging at the acclaimed art fair was Shawa’s _Walls of Gaza III, Fashionista Terorrista, 2010_. The work’s composition and rhyming title is kitschy, fun, ironic and unsettling all at the same time. The work is a screen print that originates from her own photographs; the artist herself explained to me that this work is a “tongue-in-cheek look at how images are broken up.” Shawa, whose many works are owned by the British Museum, explained that the person wearing the Keffiyeh in _Walls of Gaza III, Fashionista Terorrista, 2010_ “is a young man. However, the statement is about the imagining of Palestinian men or women, and how people are classified according to whose side they are on.” She continued; “in actual fact, the person in the picture is one of my nephews.”

The Keffiyeh, which became a symbol for resistance in Palestine, according to Shawa, “also became a fashion statement on the High Streets of all the capitals of the world and is sometimes worn by people who have no clue as to its symbolism; hence the irony!” To reinforce her idea that images are broken up to produce new meanings in order to become globally circulated, the person wearing the Keffiyeh is wearing a jumper embellished with a Swarovski-crystalled apple. This symbol of ‘the big apple’ refers to New York and Western consumerism’s adaption of the Keffiyeh’s original meaning.

The Keffiyeh has long been associated with Palestinian nationalism. It was traditionally worn by Palestinian peasants around the time of the British occupation in 1930 and was later popularised by the late Palestinian leader Yasser Arafat from the 1960’s in the continuing fight against the Israeli government. However, due to globalisation and post-modernist ideals, the Keffiyeh has been re-appropriated and commercialised for a new Western audience, with its meaning becoming displaced from its original context. Top designers, for instance, are now (and have been for a few years) capitalising on its adaption as a fashion commodity and various celebrities can be seen endorsing it. Shawa told me that the work, which includes the same image reproduced four times across the silkscreen in different colours, addresses the question “Are you a follower of fashion or a terrorist if you are wearing this scarf?” This poignant question is echoed by the work’s frame of bullets.

Described now as a ‘cool’ sign of solidarity with the Palestinian’s plight against the Israeli government’s occupation, it appears the image of the Keffiyeh only vaguely alludes to its original meaning, being displaced and replaced by a new one. As well as this, the Keffiyeh is being mass produced in China to keep up with the demand in the West; it appears fitting that a silk screen method has been employed by Shawa in _Walls of Gaza III, Fashionista Terorrista, 2010_, in the same way that Andy Warhol reproduced works in his New York factory, replicating images the way capitalist companies reproduce consumer goods.

This strange phenomenon of commodifiying ideas of freedom has not gone uncriticised by Shawa who uses _Walls of Gaza III, Fashionista Terorrista, 2010_ to express her dismay at the Keffiyehs’ adaption from a serious symbol of national struggle to a temporary Western fashion trend, since this impacts negatively on the reality of the Palestinians. Her tongue-in-cheek execution, with its jarring colours, playful title and content is a comment on the Keffiyeh’s inability to survive the flood of cheap imitations which trivialise the plight of the Palestinians for what has in reality caused a legacy of pain. It is also a comment on how this self- regulating era of hyper-capitalism is capable of monetising ideas.

The Keffiyeh, it seems, couldn’t escape the hands of capitalism. The icon of Palestinian nationalist resistance has transgressed geographical and contextual boundaries that once restricted it. The scholar, Dr Tiziana Ferrero-Regis in ‘Fashion Localisation in a Global Market’, recently stated, “The knowledge that goes into consuming the commodity through the consumption of its image is quite different from the knowledge that goes into producing the commodity.” Shawa’s work embodies this idea;_ Walls of Gaza III, Fashionista Terorrista, 2010_ triumphs in representing the interconnectedness of the East and West.

Shawa’s work poses some interesting questions. Through the irony of IslamoPop, Shawa has the upper hand. Her unashamedly vivid works show her wit and intelligence. With her symbolic frames of painted bullets, nationalist resistance is back like never before and this time it is oh so post-modern.